Apologies for the longer production time between editions. I was, after all, on vacation.

Let’s jump right into it. The title’s pretty self-explanatory.

Notes on Returning

What’s one supposed to say to a friend before their trip back home? Apparently, when that home is slipping ever-closer to fascism, it’s “I’m sorry”.

I can’t say for sure how many friends, particularly American ones, actually felt pity upon me for a 2.5 week-long vacation, but there was something about the narrative of a U.S. trip being an inherently sad exercise requiring an “I’m sorry” that didn’t sit well with me. This is also an easy thing to say as a white heterosexual male from New York left relatively unshaken by the random airport search (what a nice welcome home that was!), relative to stories of trans people fleeing states that have effectively eliminated their rights, or Latinx people being deported by virtue of being Latinx, or professors supporting Palestinians being put on a list of enemies of the state.

For one, I wanted to be there now: to feel what’s happening, hear what’s being said, what narratives are sticking. It was equally a nod to a potentially less welcoming future as to an ongoing present, one where people still get on through the day: visiting parks, seeing their loved ones, the mundane. Shouts to Emily — another American in Berlin — for this reality check and Vorfreude on the heels of her visit back home in April.

And damn, there are things that are worth looking forward to!. It’s the place I’m of. Many of my people are there. I’m allowed to miss it.

As someone who actually left during Trump’s first term, parts of me that come alive stateside will imagine alternate lives unlived. I spent an hour in Rizzoli Bookstore’s New York section and cracked open Ask a Native New Yorker, reading the ‘How to Recognize a Real New Yorker’ section, a testament to our need to argue about pizza and always be right. My heart’s tug of war between quality of life and home spilled onto the page:

“[Arguing about which place is best] is because the idea that there might be a better mode of living, right here in the city, is intolerable to us. Our New York must be the best New York, the most authentic, the one with the most heart. The extent to which New Yorkers are judgmental toward each other stems from this: the terror of knowing that someone else has found a better way to live here than we have — and that our suffering, even the smallest part of our suffering, has been wasted.”

But this is about visiting, not living. Cultural propaganda and soft power aside, there are many reasons why New York is well worth visiting, repeatedly. This isn’t exactly a mystery, but it invariably comes up in justifying every trip back. Amidst plenty of the old (a Yankee game, pizza with friends, a beach day), I manage to squeeze in something new, usually a previously off-limits experience, or a neighborhood I previously never thought of visiting. As we age, our friends bring us in on the things we’ve missed; in New York, where change is constant and culture is manufactured daily, there’s always plenty to catch up on.

Among those previously missed memos: the Five Boro Bike Tour. But that’s for later.

Climate 1: All Aboard, Courteously

When people ask what I miss, there’s always a few easy picks: a fresh bagel, a legit deli, watching sports not alone with a laptop at 1 AM.

But it’s the little things, perhaps a universal experience for those culturally displaced, that I really long for. After years elsewhere, New York public transit etiquette is firmly atop my list. I get it, every culture has getting means of what’s respectful or seen as appropriate in public, but I really fucking miss New Yorkers’ common courtesy and awareness in navigating public space.

Surprised to read we’re (gasp) courteous in New York? The ‘I’m walkin here’ crowd? Really? Let me demonstrate.

I got off the Long Island Rail Road train at the Grand Central Madison terminal, where — despite the station being brand new — escalators on the platform were broken (thankfully not THOSE escalators). The staircase, alone without its colleague, was now forced to absorb all foot traffic.

Everyone naturally, calmly, and courteously worked their way towards and up the staircase. No bumping against each other, or jockeying over space. The mass was free of conflicts over who goes first or hesitation, defined by just, well, doing what you’re supposed to do in a crowd of other people with some basic awareness and respect for those around you.

Being oblivious of your fellow commuters -- this train, after all, was a largely commuter space -- is simply not an option. This obviously takes on a different form as things get faster, and more crowded, and more awkward angles and tangles emerge in spaces bordering on claustrophobic.

Newcomers and long-timers alike in Berlin often complain of the cultural coldness endemic to the capital; that’s something I can handle. What continues to baffle the mind is not just the repeated instances of obliviousness and disregard for your fellow humans, but that they go unchecked in public transit spaces by the local population.

Again, let me demonstrate.

I was the first in a group of three exiting a train this past Saturday. Instead of waiting for all three of us to exit, one of the soon-to-be passengers got on, walking past/through the second member of our group, who was on crutches.

5 seconds later, someone on the platform — in apparent blind pursuit of the elevator — wandered straight into our crutched member’s path, then, miraculously, turned around absent-mindedly again into said path to retrieve her husband before going to the elevator. Zero acknowledgement of fellow humans, movement flows, and especially people on crutches.

This rudeness by virtue of obliviousness functions my line as to what I can tolerate and must accept by virtue of living in another place and adhering to its cultural norms. When people stand RIGHT IN FRONT of the doors of an opening train on the platform and don’t think to move, or, worse, start boarding before everyone’s gotten off, I call people out, loudly, in my native tongue. To me, one does not have the right to be completely oblivious of others’ needs when navigating public spaces. Participating means antennas simply must be up.

Sure, it may be crowded, loud, hectic, ridiculous, and filled with many a subway creature in New York. Americans talk way too loudly (our voices really do carry). My mom will still complain about when she was pregnant and people didn’t give up their seats for her and asserts, as does The Times with some pretty convincing explanations, that etiquette is now worse than ever.

But the train platform superorganism wiggles organically, sans hiccups, aloof wayward turns and out-of-place awkwardness. (In fairness, I must note that after returning to Germany, I witnessed 30 Americans take their sweet time alighting a high-speed train, despite the frantic pleas from platform staff to hurry their asses up. Perhaps they were from Nebraska.)

The etiquette baseline back home is, appropriately, pretty damn high. It comes with the bonus of genuine friendliness and sharing laughs with strangers. I can have friendly casual conversations with the train conductor, or (in Philly on the bus and trolley, especially) shoot the shit with other passengers in ways almost always culturally inaccessible (perhaps by virtue of being a non-fluent speaker) back in the DE; the lone exception, of course, is complaining.

My final public transit trip in the homeland was icing on the cake. With delays on my scheduled Amtrak journey along the Northeast Corridor (perhaps America’s only intercity route of note), I was graciously allowed to board an earlier train, and fortunate to have staff running the train that were equal parts cool, chill, and communicative. The conductor’s announcements turned what’s normally a fuzzy annoyance into a performance, ala a radio DJ introducing the upcoming track. He signed off each announcement like a smooth-talking Kool-Aid man:

“Next stop: Newark Liberty Airport NEW JEEEERSEEEY

OHHH YEAAAHHH”

Climate 2: On two wheels

I did lots of biking this trip. You can decide whether it was some attempt at penance (forgive my diction, was at a Catholic wedding) for many unnecessary two-minute drives to the train station, or countering the inevitable effects of an All-American diet for 2 weeks.

It’s refreshing how biking in major cities has evolved to even being a possibility since I’ve left the country. Yet I returned to Europe with mixed feelings about the prospect of an American biking revolution, and some Vorfreude for being in a bike-first city that actually kinda works.

Let’s start on a really high note: 200 feet up, crossing the Verrazzano Bridge.

This was the surreal, well-earned conclusion to the Five Boro Bike Tour, an annual celebration of biking completely unbeknownst to me until this February. Four million points to John for the invitation to join his team and hang for what turned out to be a fantastic day, and another four million to Liam for tuning up his bike, which he so graciously lent me for the occasion.

The tour — notably not a race — takes 30,000+ riders across much of New York City (the Bronx and Staten Island feature very lightly here, I’m afraid), shutting down massive avenues, 5 bridges, and 2 highways, much to the ire of other locals. Well, screw ‘em. Biking needs more than a whole day to reign supreme.

Southbound BQE Traffic is LOSED

I had the pleasure of attending a Futures workshop last year from Dr. Stuart Candy, who presented one class’s ‘monument from the future’ of New York City in 2030. This was on the heels of congestion pricing getting repealed, so it certainly stung at the time to see their creation: a monument to ‘the last car in New York City’ in Times Square, full of pedestrians admiring the end to this ecologically disastrous form of transportation.

A day like the Five Boro Bike Tour has the intent of making that future possible. It’s energizing (we had literal cheerleading squads along the route in Manhattan), affirming, and miraculous. How often do you ascend a bridge on-ramp, or a gradually sloping highway designed for something with several hundred horsepower, instead of one human power?

This appreciation for scale and potentially rewriting those relationships to infrastructure via the bicycle is super exciting. Anyone who’s been to Tempelhofer Feld in Berlin, and ridden their bike or walked down a former runway designed for planes, gets a taste of that. But never had I experienced that ant-level tinyness, yet feeling somewhat mischievous via some spatial renegotiation takeover, quite like the (albeit temporary) first Sunday in May.

I was about to write a whole section about how incredible the experience of biking in New York had been, with so many surprisingly awesome lanes, even a bike street with 10 mph limits for local traffic only, which I’d never seen before.

Those glowing notions were laid to rest in Western Queens.

I attempted mixed mode commuting in Long Island City during one of the other 364 days of the year, roughly following a section of the Five Boro Bike Tour route, in reverse, from a few days before. It was a touch naïve to think this trip would actually have worked out: perhaps my baseline had shifted after another glorious bike ride (this time over the Williamsburg Bridge to Greenpoint); perhaps I ought to have punted said baselines into Newtown Creek.

I planned, like an idiot, to actually attempt using the Long Island Rail Road from Long Island City to get back to Long Island. To the non-local reader, this decision may appear to be self-evident. Use public transport in the city of a place to reach the rest of it. What could go wrong?

One of the things I love about Berlin so much is the multimodal utility of its transit system — i.e. things connect to each other, making transfers from one type of transit to another relatively seamless. Well, when you try taking the LIRR from LIC, seamless sure ain’t the description.

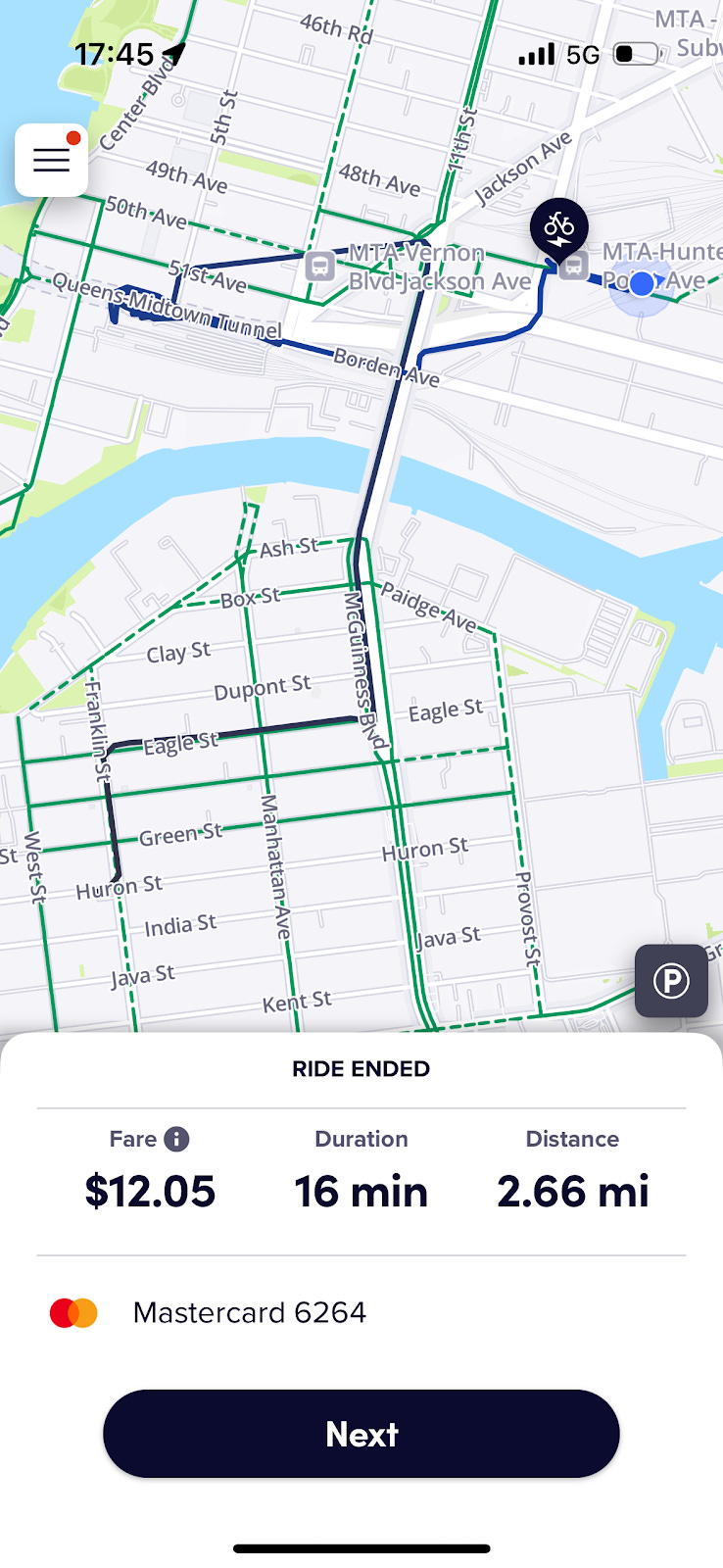

I rented an e-bike to try catching one of the 3 trains all day (they only run rush hour evenings) departing from LIC. Check out this ridiculous route in futile pursuit of both finding the station entrance (tucked away in an industrial lot) and finding a dock for my CitiBike (a mission I only began after finding the station entrance, which, spoiler, was 4 blocks from the nearest dock).

By this point, it was clear I wasn’t going to make the train, so I abandoned ship and rushed to the next station on the line, Hunterspoint Avenue, via a highway on-ramp and an unnecessarily close brush with death. Another few minutes avoiding craters potholes, then searching for a dock (only successful after biking in reverse), and I somehow managed to beat a literal train by a full 12 minutes to a station only 2 miles away.

Oh, and this 16-minute bike ride in search of nonexistent multimodality cost me $12. If this doesn’t tell you something’s wrong with our transport system, what will?

Philly is a reality check on what we think progress is. It asks you to surrender to its weirdness and shortcomings; in return, it will embrace yours, perhaps with a $5 Citywide Special.

Biking, respectfully, is among those shortcomings. While the politics are changing somewhat around biking, the fact remains that America’s 6th-biggest city — a flat, dense one no less — has a paltry 30 miles of protected bike lanes relative to 600 in NYC.

Biking largely attempts to happen on shared streets in well-off neighborhoods where bikers have the privilege of being able to participate in traffic; even where there are dedicated bike lanes (like Spring Garden St, one of the rare major east-west thoroughfares cutting across Philly), cars don’t necessarily play ball, which isn’t necessarily any different than drivers in New York, but worse without anywhere to hide for cover. The head of Penn Urban Studies, who I got to chatting with during our alumni walking tour through FDR park, has simply given up on biking after getting hit three (!) too many times.

Indego, Philly’s dock-based bike share system, perfectly epitomizes the city’s shortcomings. My friend and former supervisor Adam’s rationale for cancelling his Indego subscription was it being “too Philly”; in other words, you can’t quite figure out whether or not it works.

In my 4 days of using the system, Indego failed to recognize when I returned my bike at a dock on 3 separate occasions. Their solution is hilariously makeshift: texting a picture of the bike to a customer service number and sharing some details about the bike before they can make a manual inspection.

Imagine how wildly inefficient that is! How often do bikes not dock properly? One of those trips ended at 1 AM; apparently, my bike was accruing charges the whole night until an agent got on during the morning shift and validated the previous night’s events with me. Completely insane.

I’ll try biking again next time in Philly, but probably won’t be looking forward to it. When the Urban Studies people don’t wanna bike, things are in a poor state indeed.

Nod to collective brilliance

Well, this sure isn’t going to Indego. Or the Philly deli sandwich I ate while waiting out a power outage on the Market-Frankford Line and flash flooding warnings before the wedding (the skies did eventually part, in case you were wondering).

New York’s A Train gets my nod this edition. It’s a testament to a level of transit ambition from a bygone age, and to transit planning ingenuity that genuinely sets the NYC Subway apart from its peers.

The route is astoundingly lengthy: 32 miles (52 kilometers), stretching from the northern tip of Manhattan to the most southeastern corner of Queens, literally diagonal across NYC. As my mother reminded me, it formed the bulk of grandma’s postwar commute to nursing school at Mount St. Vincent’s in Riverdale, all the way from South Ozone Park.

Paying coincidental Mother’s Day homage to both of them, I boarded the train at 200th Street, practically teleporting 166 blocks south to my train at Penn Station, where I frantically dashed from platform to platform in (successful) pursuit of the 5:47 to New Hyde Park .

It’s all made possible by a forward-thinking investment in parallel local and express tracks, which the original investors in NYC’s subway systems built in tandem under its broad avenues. This way, you get the A-C-E trains, with the C running local from 125th Street in Harlem to Euclid Ave in East New York, and the A making a quarter of the stops along that stretch of its route with some bonus stretches on either end (like 200th Street in Inwood and 111th Street in Ozone Park, for example).

I wish construction that ambitious felt a bit more possible these days. Too bad it’s $2.5 billion a mile. Maybe they’ll learn! Maybe a Transit Superhero Englishman can save us!

Something I watched recently

“Emilia Pérez? Oh, you haven’t seen Emilia Pérez? Whoa… Emilia Pérez!!”

These were the words of Roy, a former professional film critic in his 80s, baffled by my failure to visit our local movie theater and sufficiently engage in culture. An elderly man, keeping up with the times, conscious of his limited time left to appreciate the world and its creations, recommended this film to me as an absolute must. What am I to do but go see it?

Predictably, us hermits missed Emilia Pérez in theatres, and I was resigned to watching a film about a transgender Mexican drug kingpin hunched next to a stranger on United Airlines.

(An aside: before every new film, you were forced to watch the same meaningless ad from a U.S. accounting firm, featuring two mid-level employees about my age speaking in cookie-cutter generalities about their firm’s above averageness. Immediately, this got me thinking about the kind of person our country is currently intent on producing: some accountant able to smile arrogantly and shallowly on camera for an overpaid ad, pre-juxtaposing him to the caliber of cultural explosion and multidimensionality from the actresses in Emilia Pérez).

Anotha one where I needed the credits to compartmentalize continued whiplash by way of a roller coaster plot, which I of course will not ruin here for those who, too, have failed to uphold their cultural duty (or are boycotting the film in the wake of Karla Sofía Gascón’s comments).

Beyond the cultural and literal explosions, Emilia Pérez embodies bravery in confronting totally corrupted politics that blows me away, especially given literal life and death stakes. We felt this in Oaxaca in 2023: our tour guide, a courageous student in his early twenties emulating the late artist-activist Francisco Toledo, spoke truth to local corruption and gentrification, despite being in constant danger from public officials. I often ask myself if I would be capable of the same.

Emilia Pérez provides a glimpse into the Mexican narco-corruption state, and greed of the hyperconnected upper class. In one scene, at a fundraiser gala, the lawyer protagonist stops time to dance aggressively on everyone’s tables, poking at the corruption and hypocrisy of the pretend do-gooders in attendance, their mediocrity of character revealed. For one: The Minister of Education with jets, an expert in shell companies more than young peoples’ dreams.

Us gringos can’t even get around to criticizing a President accepting a foreign jet bribe and enriching himself through his own cryptocurrency, waving it in our faces as a Republican House pushes the most significant upward transfer of wealth in history. The corruption is disgusting; the mediocrity in our collective character disillusioning.

We have plenty to learn from our neighbors. Do we mobilize against tyranny? Step up when lines are crossed? It will make a difference in how far we slip into authoritarianism.

Place I traveled to recently: Upper Manhattan

The sun was shining for my last full day in New York, so it was about time for a proper travel day in visit mode.

Upper Manhattan — way past Upper East or Upper West — won the meaningless prize of a place I would visit on a Monday afternoon. After successfully recreating the Central Park stretch of the Five Boro Bike Tour, popping out in Morningside Heights to visit St. John the Divine Unfinished and Riverside Park, I made my way uptown to Washington Heights for a Dominican oxtail lunch.

This was all in service of somewhere I’d already visited and was eager to reencounter: Fort Tryon Park, which I put up against any park in the Five Boroughs. It’s got it all: history (Revolutionary War Fort!), topography (bedrock hills, rare in NYC), scenery (views of the Hudson River, the George Washington Bridge, and, if you find the right spot, the Tappan Zee Bridge), gardens, and a stunning museum (The Cloisters). It’s pristine, yet a contradiction: it only exists in its current state because of the Rockefellers’ private oil money (not just with this park, which happens to be a perfect example).

Despite the relative remoteness by NYC standards, noise proves inescapable: flights of all varieties buzzing overhead, loud locals, construction, sirens blaring, buses and cars from the streets within and highway below. Manmade interventions are required to stave off the manmade sound. It’s the same anywhere I’d gone on this trip, and upon reflection, my entire life in New York. Even the beach — our local definition of ‘nature’ — has got flights, and unnecessarily loud conversations, none of which one can simply put on mute. I find it hard to unwind in a sound stimulating environment. It keeps me constantly on somewhat of an edge; research on ‘noise pollution’ in NYC backs this up.

During my stroll in the park, an old friend of mine sent a mother’s day wish to pass onto my own mom and a heavenly variety to send to my grandma, a very touching gesture in a way that really old friends can. I continued up the path en route to a flower garden. There, just as I had in my many visits home, a grandson in his 20s was spending the afternoon with his grandma in her 80s, a former pastime of cracking jokes and reminiscing that now only exists in memory. It hadn’t truly settled in until just then that this was the first among visits not to have a visit with her on the itinerary. (Note to mom: I was sitting next to lilac bushes, by chance, while writing this.)

Grief really can stop you dead in its tracks.

Pennies for your thoughts

This edition’s batshit crazy headline

Train Daddy is back. (This crazy GREAT news!)

Random notes

I came across this quote on advertising from the Secret Life of Groceries (a worthy runner-up in this edition’s read/watch section): “Gradually, I came to realize that modern advertising could be seen less as an agent of materialism than as one of the cultural forces working to disconnect human beings from the material world” (113).

Nonetheless, I was struck with how effective American marketing is. Check out these ads in the subway for BackMarket, something that seems almost un-American in its anti-consumption, fight against planned obsolescence, recycling ethos, almost parachuted in from, well, Germany.

Conversely, it’s remarkable how ineffective American water fountains are. It’s a complete and utter crapshoot whether they’re working or not. Low key drinking water is essential public infrastructure. It’s an odd experience walking up to one with hopes to quench your thirst suddenly activated after having spotted said fountain, only to be met with a rush of disappointment both in unmet craving and failed urban services. Might be one for a future article…

Something great I’ve eaten

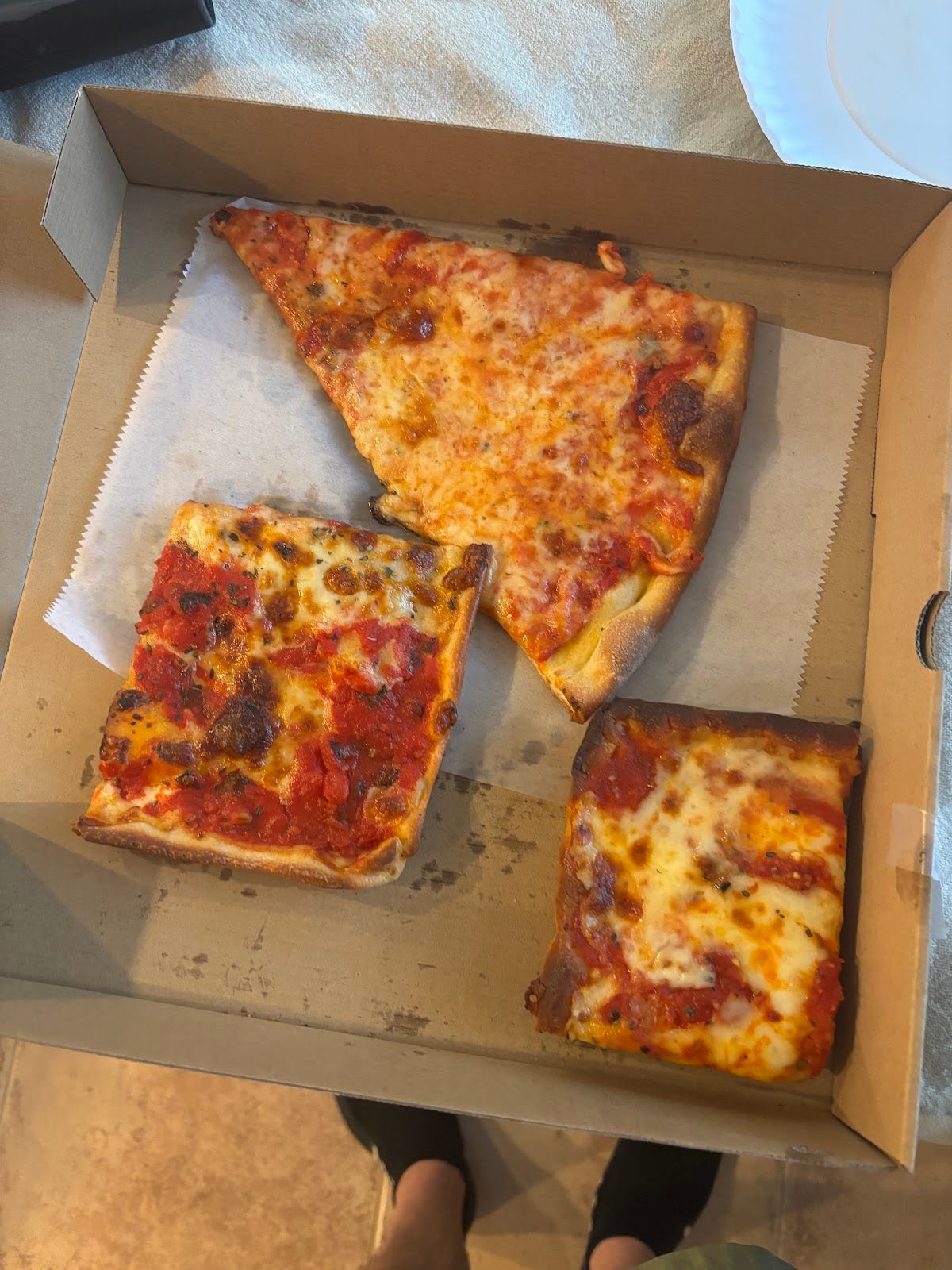

Shouts to the oxtail, and tacos from Taqueria Ramirez in Greenpoint, but there’s only one correct answer for this edition: a grandma slice from Village Pizzeria in Floral Park.

She’s on the bottom left (Credit: The Corteos)

An ode to the penny

Perhaps this constitutes going overboard. In Philly, my lone museum visit was to the actual United States Mint, the largest coin factory in the world smack dab in the middle of Independence Mall. In case you’re wondering, this was 100% intentional for Connecting Climates, and I am so glad I did it. Hands-down my best museum this year.

Fellow history nerds would love the place. Among many, many factoids:

The Founding Fathers’ debates about founding a mint were all explicitly tied to freedom from other nations, who warned that another nation— should an American mint be outsourced to it — would have tremendous leverage if eventually at war with the United States. A prescient lesson for today indeed.

There’s a United States Mint Police. Their role beyond forcing tourists out of the building at 4:15 PM is beyond me.

The Mint mints five different types of coins: circulating, National medals, annual collector sets, commemorative coins, and bullion coins.

Circulating gold coins went for as much as 10 dollars back in 1842! I saw coins thicker than my pinky, others worth over a thousand bucks.

“Hobo nickels” had their heyday from 1913-1960s; hobo was originally a term for those who traveled by freight train in search of work. Many of those hobos were using their craftsmanship to make stunning hobo nickels, which they bartered.

Care to learn the steps to coin making as you walk over the actual factory?

Art: Artistic design is the first step in the coining process

Die making: The die shop makes the tools that strikes the coins

Blanking: In this department, round blanks are punched out of metal strips using extreme force.

Annealing & upsetting: This is where the blanks are prepared for striking.

Striking: Also known as coining, this is where the design is added to the planchet (so many new words!).

Inspecting: Each batch must meet United States Mint quality standards.

Bagging: The finished coins are packaged for their journey to the Federal Reserve Banks (Philly’s is across the street!)

The Treasury Department may have just placed its final order ever of ‘blanks’ (I know what blanks are now!) set for production next year. But, as of my visit, the Philadelphia Mint alone had produced 995,656,206 coins this year, 396,909,367 of which were Pennies!

An ode to the penny indeed.